When broadcasting in the vernacular language of their sponsoring nation, international broadcasters target

(although not exclusively) members of their respective diaspora—so-called "ethnic" minorities abroad.

Germany's Deutsche Welle, for instance, offers German-language radio and television services that address

Germans and people of German descent living, travelling or sojourning in another country.

[1] Such groups are

often too small or otherwise inaccessible to be adequately covered by a nationally representative survey.

However, they may be of key interest in terms of niche broadcasting, marketing campaigns, or public diplomacy.

[2]

When investigating how descendants of German migrants negotiate their particular "German" identity, or

"Germanness", in the diaspora, and which media are being used in this process, the author became aware of the

German community

[3] in Chile. That South American nation's history of immigration from German-speaking countries

(Austria, Germany, Switzerland) dates back to 1846 and 1852 when the first groups of settlers arrived in its

Patagonian outposts. These immigrants, mostly farmers, craftsmen and traders, were seeking better living

conditions abroad. They settled in coastal towns and founded a large number of mainly villages and smalltowns

in the hinterland of what was then a "frontier" region: situated between these southern colonies and the

territory controlled by the Chilean government in Santiago (some 900 kilometres to the north) was a vast

area still ruled by the indigenous Mapuche nation. Today, the German-Chileans' core settlement area forms

the country's 10th administrative region, Región de Los Lagos (Lakes Region).

In 2002, Chile had an estimated German-speaking population of ca. 20,000—that is hardly more than 0.1%

of the country's total population of ca. 15.1 million.

[4] Another rough estimate states that ca. 150,000 to

200,000 Chileans have some German ancestry.

[5] The number of Chileans actually speaking the German language

has been in decline ever since the end of World War II, the reasons being increasing intermarriage with

non-Germanophones, ongoing assimilation, and, one may guess, a general process of cultural/linguistic

homogenisation in which electronic mass media have played their part.

Along with these processes of self-definition and belonging, which are truthful on their own terms, we may

uncover "inventions of tradition"

[10] (for example, in local heritage museums) and aspects of "imagined

communities"

[11] (e.g., the overall concept of being a "German-Chilean": assumed and hardly ever questioned). In

such a context, German-Chileans may be seen as people whose deterritorialised Germanness "clearly coexists with

other national identities as well"

[12], most clearly of course a Chilean identity—an identity which, however, is

a multiple and disputed one itself.

Official histories published by the German-Chilean Federation tended to stay clear of such questions

[13]; these

have been touched upon only recently.

[14] In these official historical accounts it is evident that membership of

the German-Chilean community comes by way of lineage. If one is to pragmatically accept this notion for a start,

researchers have one handy and inexpensive tool at their disposal to identify members of the German-Chilean

subpopulation: consulting the regional telephone directory.

[15] As it turns out, Chile's system of listing names

in directories is of particular help for guessing at a person's lineage. In Chilean telephone books, name

entries follow an Hispanic formal structure:

"[given name 1] [given name 2] [patrilineal family name] [matrilineal family name]"

The patronym is the main family name. The use of the (non-hereditary) matrilineal family name is, in informal

usage, optional (alternatively, it may be abbreviated), as is the use or the existence of second or additional

given names. The formal structure of telephone directory entries thus reveals, up to a point, a genealogy of

German names and, linked with that, a possible (though not necessary) membership of the German-Chilean

ethnic/cultural community.

[16] The relevant entries may subsequently be used for various research purposes

(telephone or personal interviews, postal surveys, etc.). In South Chile's population, one may discern four

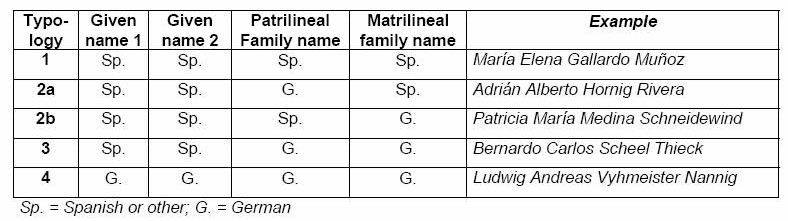

major name typologies (see Table 1).

Table 1: Name typologies of Chilean telephone directory entries

(with specific reference to German names)

Señora Gallardo (Typology 1) might identify herself (if she were interviewed) as a member of the German-Chilean

community and even be conversant with the German language, but based on her all-Spanish names she would, for

formal and perhaps unjustified reasons, initially be excluded from being contacted for the purposes of a study

in the context of identifying members of the German-Chilean subpopulation. The directory entries of Señor

Hornig and Señora Medina, on the other hand, show some German lineage—at least one parent seems to have been

of German stock (Typology 2a and 2b—or Typology 2 when combined). Señor Scheel inherited German family names

from both parents (Scheel and Thieck) although he uses Spanish-sounding given names—Bernardo and Carlos

instead of Bernhard and Karl (Typology 3). Señor Vyhmeister's entry (Typology 4) almost reads like one from

Germany; with his typical German, non-Hispanicised names—Ludwig and Andreas instead of Ludovico and Andrés

as given names—he is most likely to identify himself as a German-Chilean community member.

Again, it should be stressed that mere name characteristics per se do not prove membership of an ethnic or

cultural community but they may point in that direction and may serve as formal search criteria for drawing a

sample of a particular diasporic subpopulation. Moreover, it is obvious that these nominal criteria should also

work when creating samples of other non-Hispanic immigrant communities, e.g., Irish, Scottish, Croatian,

Italian, etc.—family names like McDonald, McIver, Vukić or D'Allessandro have a relevant incidence in

Chilean telephone directories as well, though to a lesser degree in the Lakes Region where German names play a

prominent role.

[17]

Target and survey population

For a proposed postal questionnaire survey of, and subsequent personal interviews with, members of the German-

Chilean community living in the Lakes Region, a sample of that area's German-named subpopulation (Typologies

2-4) shall be drawn. As official registries of residence are not accessible, sampling shall be based on the

regional telephone directory which contains name entries as described above plus home addresses.

[18]

The area's telephone directory lists main connections (no cell phone numbers) within the 10th and 11th

administrative regions. Entries are classified by cities and towns, totalling 106 municipalities of which

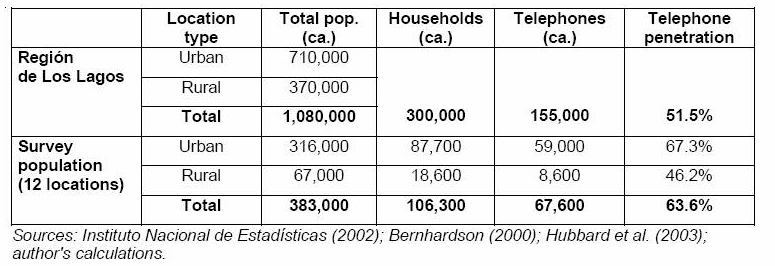

those situated in the thinly populated 11th administrative region can be excluded. The 10th region, De Los

Lagos, has a population of ca. 1.08 million (ca. 7% of Chile's total population) living in ca. 300,000

households (based on the average Chilean household size of 3.6 persons). Of these, ca. 155,000 have fixed-line

telephone connections and ca. 153,000 a mobile phone (often both). The rate of (fixed-line) telephone ownership

in Chile is 51.5%, an almost identical percentage applies to households in the Lakes Region.

[19] Still, some rural

villages there have only a handful of listed land-line telephones, the majority of these sometimes obviously in

communal use, judging from the non-individual listings. Larger towns and cities show a higher telephone

penetration (see below).

The infrastructure data clearly indicate that no sample based on the region's telephone-directory entries can

be considered to be representative. However, such a sample may prove acceptable for undertaking a target-group

survey of the German-Chilean community in De Los Lagos, or generating contacts for individual in-depth

interviews. Members of that community traditionally belong to the better-off strata of the population with a

higher chance of telephone ownership compared to the average total population.

Of the ca. 100 municipalities located in the 10th administrative region, 12 cities and towns were considered

for sampling. These 12 places are distributed across the region. Historically, they are main settlement areas

of the German-Chilean subpopulation; most of them have been founded by German colonists in the 19th century.

Three of these locations were classified as "urban" (i.e., populous enough as to be featuring a minimum of 50

columns of 80 listings each in the Lakes Region telephone directory). The remaining nine settlements were

classified as "rural".

[20]

The "urban" locations in the sample have an estimated total of ca. 316,000 inhabitants or ca. 87,700 households

(based on the rough assumption that the national average of 3.6 persons per household does apply here as well),

and ca. 59,000 listed fixed-line telephones, resulting in an above-average telephone penetration of 67.3%. The

selected nine "rural" locations have a total population of ca. 67,000 people (ca. 18,600 households) and some

8,600 listed telephone connections which results in a below-average telephone penetration rate of 46.2%.

[21] The

overall telephone penetration in the selected settlements is 63.6%, a rate considerably higher than the Chilean

national average.

Table 2: Population and telephone infrastructure data, Lakes Region, Chile (2002)

The final survey population is thus based on listings in the Lakes Region telephone directory (2004 edition)

pertaining to 12 selected target locations, comprising of a total of ca. 67,660 entries in 864 columns, that

is 823 complete columns (80 entries each) plus 41 incomplete ones (less than 80 listings) as printed.

Sampling plan

The aim is to generate a sample of 1,000 German-Chileans with their names and addresses. For this end, all

selected columns of the telephone directory shall be systematically searched for individual entries with names

indicating German descent according to Typologies 2a, 2b, 3 and 4 (see above) in random sequence. The plan is

to search for one entry belonging to Typology 2a in the first randomly selected column, one entry of Typology

2b in the second randomly selected column, one Typology 3 entry in the third one, and so forth, starting with

the topmost entry in each column.

Since it is not possible to arrive at the desired sample size of 1,000 entries in a single perusal of all 864

columns, a second run will be necessary. This shall be effected in reverse order, i.e., by selecting bottommost

entries in each column. Should third and fourth runs be necessary, relevant second-from-top and next-to-bottom

entries (and so forth) shall be selected until 1,000 cases have been selected.

This particular sample size has been chosen with regard to being sufficiently large for a quantitative postal,

face-to-face, or telephone survey; however, no information could be found as to interview refusal or

questionnaire reply rates within the German-Chilean community as systematic surveys of this kind seem to have

no precedence. For qualitative research, the process described above may be applied for randomised interviewee

recruitment as well, though the sample size may then need to be reduced considerably, depending on the study's

objectives.

Testing the sampling plan

In order to assess the suitability and appropriateness of the sampling plan, a test consisting of a

unidirectional single perusal of all 864 columns has been undertaken. The aim was to find out how many entries

with a German name typology would be selected employing the random sampling plan described above, and how these

would be distributed typologically.

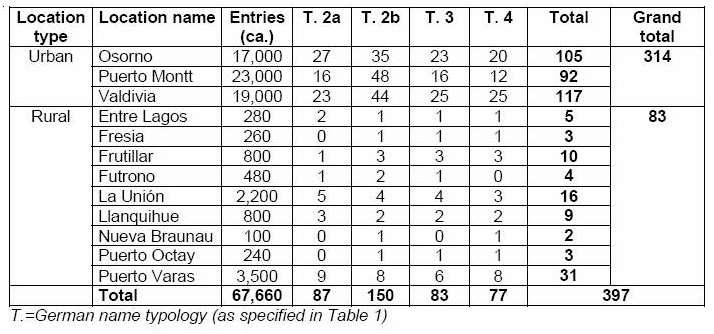

The completed test run resulted in a total of 397 selected cases, or 0.6% of directory entries in the 12

selected locations. Exhaustion levels of German names are at 0.95% for "rural" cases and 0.53% for "urban"

ones. "Rural" cases (83) make up 21% in this test sample; they are somewhat over-represented compared against

their incidence in the overall number of inhabitants (17%) and telephone directory entries (13%) in the 12

selected locations. Accordingly, the test sample is made up of 79% of "urban" cases (314 in total) which means

these are under-represented vis-à-vis the proportion of "urban" inhabitants (83%) and directory entries (87%)

of the survey population. This skew towards rural hits may be explained by South Chile's 19th century

immigration patterns in which German farmers had been allocated tracts of land "on the frontier", "in the

wilderness", which is where they founded villages and towns. In addition, as noted before, German-Chileans

might have a higher chance of telephone ownership compared to the average total population due to higher

economic status, though this assumption still needs to be reasserted.

All in all, however, the distortions outlined above seem to be acceptable when keeping in mind that the above

values are the result of a test run and that representativity is not at stake here anyway. Table 3 contains

the results of the trial sampling procedure.

Table 3: Random sample of German-named telephone directory entries

in Lakes Region, Chile (2004)

What is striking is the relatively high number (150) of Typology 2b cases (German matrilineal name—optional

use only). Whether this is statistically relevant, or relevant at all, should be assessed only when a sampling

procedure of the type described above has been completed, yielding a full 1,000 cases. In the meantime, when

one combines Typologies 2a and 2b and views them in relation to the other two name typologies, the ratio of

Typologies 2 to 3 to 4 is roughly 3:1:1, or 60:21:19%. Genealogically speaking this is quite a natural

distribution.

One may assume, therefore, that a sampling plan for the German-Chilean population as outlined above is viable

and may yield a useful sample. With some caution (and without wishing to put too much strain on the concept of

representativity) one could argue that the final sample might represent South Chile's German-named minority

adequately, the main drawback being Chile's relatively low overall (fixed-line) telephone ownership rate.

Conclusion

The sampling plan for the German-Chilean minority subpopulation which was introduced in this article can

certainly be adapted to other ethnic/cultural minorities as well, at least in Chile or in countries where

similar conditions exist. Such subpopulations, whatever their definition, may be captured quite adequately by

a directory-based sample, one may argue, and at very little cost as far as sampling is concerned. Applications

range from postal, face-to-face or telephone surveys to qualitative inquiry and marketing campaigns. Of course,

all limitations that apply to any sampling approach based on telephone directory entries (How many telephone

connections are there? Who owns a telephone, who doesn't? Who is listed, who isn't? How reliable are those

directories in the first place?, etc.) need to be considered as well. Given Chile's particular situation in

terms of infrastructure and economic and social stratification, these limitations are not to be underestimated.

Some shortcomings of the sampling plan may need to be reconsidered too. Selecting 12 particular settlements

(out of almost 100) was pragmatically and ethnohistorically justified but might have distorted the resulting

sample nevertheless; to which degree we do not know. In any case, full randomness could be attained by

including all settlements of the Lakes Region as far as they are featured in the telephone directory.

On the upside, the Chilean (Hispanic) system of listing telephone owners with their full family names

(patrilineal and matrilineal) offers the opportunity to catch even subpopulation members who would often

shed or abbreviate their matrilineal name in public use, thereby making it near impossible to identify this

aspect of their descent under normal circumstances. As we have seen above, it is exactly the corresponding

name typology (2b) which formed the largest subgroup in the test sample. However, the assumption that simply

by carrying a name inherited from some more or less distant immigrant ancestor the bearer should automatically

feel a certain form of "belonging" to that ethnic or cultural group must be contested. Therefore, the sampling

plan introduced here is only one of several possibilities to approach the concept of the existence of "ethnic"

or "cultural identity". Results of additional qualitative ethnographic fieldwork should indicate if the

assumptions based on name typology and ethnic/cultural membership sketched in this article are founded at all.

Notes

[1] One may be surprised to find German a language rather frequently featured on transmission schedules of quite a number of international broadcasters; see Hélène Robillard-Frayne: Survey of CIBAR members concerning developments in their organizations. In: Deutsche Welle (ed.): An essential link with audiences worldwide. Research for international broadcasting [Proceedings of the CIBAR annual conference 2000]. Berlin: Vistas, 2002, pp. 41-57.

[2] For a successful, yet expensive, example of an "ethnic" target-group survey see Alice Buslay-Wiersch: Researching small ethnic target groups. Assessing the market potential of "GERMAN TV" among German-Canadians. In: Oliver Zöllner (ed.): Beyond borders. Research for international broadcasting (= CIBAR proceedings, Vol. 2). Bonn: CIBAR, 2004, pp. 117-126.

[3] For an early critical assessment and theorisation of the concept of "ethnic" community, or commonality, and related phenomena, see Max Weber: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriss der verstehenden Soziologie. 5th ed. Tübingen: Mohr, 1972 [1922], pp. 234-244.

[4] See the 2002 Chilean national census data, available from the Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas at http://www.ine.cl, and Peter Rosenberg: Deutsche Minderheiten in Lateinamerika, retrieved from http://www.kuwi.euv-frankfurt-o.de/~sw1www/publikation/lateinam.htm, downloaded 14 December 2002 [in similar format now available at http://www.academia.edu/26669839/Deutsche_Minderheiten_in_Lateinamerika].

[5] See Rosenberg (as in footnote 4) and the often sketchy estimates provided by the "Ethnologue" database at http://www.ethnologue.com.—For the remainder of this article, "German", as in "German-Chilean", etc., refers to origins in any German-speaking territory, not exclusively Germany. Europe's changing political boundaries during the 19th and 20th centuries make clear distinctions nigh impossible anyway; consider, for instance, the immigration of German-speaking Bohemians.

[6] For a revealing Hong Kong/Chinese example of this "hyper-reality" of cultural reproduction, see Eric Ma: Mapping transborder imaginations. In: Joseph M. Chan/Bryce T. McIntyre (eds.): In search of boundaries. Communication, nation-states and cultural identities. Westport, London: Ablex, pp. 249-263 (255).

[7] Malcolm Chapman/Maryon McDonald/Elizabeth Tonkin: Introduction. In: Elizabeth Tonkin/Maryon McDonald/Malcolm Chapman (eds.): History and ethnicity (= ASA Monographs, No. 27). London, New York: Routledge, 1989, pp. 1-21 (11).

[8] Chapman et al. (as in footnote 7), p. 15.

[9] Discourse's conceptual links with hegemony and ideology are obvious; see James Watson: Media communication. An introduction to theory and process. 2nd ed. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, pp. 50-51.

[10] See the many illuminating examples in Eric Hobsbawm/Terence Ranger (eds.): The invention of tradition. Cambridge, London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

[11] See Benedict Anderson: Imagined communities. Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Revised edition. London, New York: Verso, 1991.

[12] Diana Forsythe: German identity and the problem of history. In: Tonkin et al. (as in footnote 7), pp. 137-156 (147).

[13] Liga Chileno-Alemana (ed.): Los alemanes en Chile en su primer centenario. Resumen historico de la colonización alemana de las provincias del sur de Chile. Santiago de Chile: Liga Chileno-Alemana, 1950; Emil Held/Helmut Schuenemann/Claus von Plate (eds.): 100 Jahre deutsche Siedlung in der Provinz Llanquihue. Festschrift. Santiago de Chile: Condor, 1952; Liga Chileno-Alemana (ed.): Pioneros del Llanquihue. 1852-2002. Edición conmemorativa de los 150 años de la inmigración alemana a Llanquihue. Santiago de Chile: Liga Chileno-Alemana, 2002.

[14] See the excellent and comprehensive account of German immigration to Chile by Andrea Krebs Kaulen/Ursula Tapia Guerrero/Peter Schmid Anwandter: Los alemanes y la comunidad chileno-alemana en la historia de Chile. Santiago de Chile: Liga Chileno-Alemana, 2001, which, for the first time, explicitly includes not only Protestant and Catholic, but Jewish German-Chileans as well. The book also adequately outlines German community members' roles in the development of the Chilean nation.

[15] Compañía Nacional de Teléfonos, Telefónica del Sur [ed.]: Guía [de Teléfonos] 2004. Regiones X - XI [de Chile]. Sine loco: Telefónica, 2004.

[16] Telephone directories in neighbouring Argentina, for example, do not permit this kind of detailed guesswork as they only feature given and patrilineal (main) family names; see Telefónica [ed.]: Guía Telefónica Argentina 2004. San Carlos de Bariloche. Sine loco: Telefónica, 2004.

[17] Typical German-Chilean family names can be looked up in the listings of immigrant settlers documented in: Liga Chileno-Alemana (ed.): Pioneros del Llanquihue (as in footnote 13).

[18] See Compañía Nacional de Teléfonos... (as in footnote 15).

[19] See the National Census data of 2002 at http://www.ine.cl, in part also reprinted in Compañía Nacional de Teléfonos... (as in footnote 15), p. 8/9. Chile's average monthly income per capita (2003) is 305,749 pesos (ca. US$516). Inter-regional variances are considerable: the average monthly income in the Lakes Region is 264,786 pesos (ca. US$447); see Catalina Allendes E.: El salario promedio de un chileno varía hasta 45% según la región. In: La Tercera (Santiago de Chile), año 54, número 19,651 (21 March 2004), p. 43.

[20] In the Lakes Region, 66% of the inhabitants live in an urban area, 34% in rural conditions, though no precise definitions of what "urban" or "rural" means in Chile could be found.

[21] Population figures of cities and towns were calculated on the basis of reliable travel literature, most notably Wayne Bernhardson: Chile [and] Easter Island. 5th edition. Melbourne, Oakland, London, Paris: Lonely Planet Publications, 2000; Carolyn Hubbard/Brigitte Barta/Jeff Davis: Chile [and] Easter Island. 6th edition. Melbourne, Oakland, London, Paris: Lonely Planet Publications, 2003.